Endings in comic books aren’t an easy thing to engineer – especially when you have a successful series on your hands. Hellboy, and the expanded Mignolaverse is one of those dream creations for a writer and an artist – something that is elastic enough to encompass pretty much anything the writer wants to talk about.

Endings and beginnings in comics are now normally cheek by jowl, and the transition is an event that is marketed, and engineered to allow one writer to jump ship and another to come on board. It is also often accompanied by titles being siloed and new ones being launched. They have massive tie-ins that require a reader to buy multiple titles if they really want to follow along and get all the narrative quirks. It can be a bit overwhelming sometimes, and with the continual reboots, keeping track of chronology and where a character is at can be a nightmare. The yearly event annoys some readers, because it feels gimmicky; Hellboy doesn’t do this. When you get a new Hellboy it takes the character somewhere new, but somewhere informed by where he has been before.

“I thought, If we’re going there, let’s just go there now. So, yes, we’re wrapping up Hellboy in Hell.” ` Mike Mignola

It’s been twenty odd years since Hellboy debuted. He was born from a sketch at a comic convention, and who would have guessed he would have traveled so far and done so much? I recall buying those early stories and finding it a lot harder to get hold of the books – the movies changed that. And it’s funny, because the name Hellboy, Mignola says, has presented its own marketing challenges … having the word Hell on anything raises flags.

When characters die in comics it usually paves the way for some convoluted ret-con where a whole series of dominoes are untoppled, and often a whole universe of ghosts in the machine are pulled out to reestablish the status quo, or maybe a slightly off-kilter version of it. Said version will roll along, usually for a year, paving the way for the next multi-title tie-in and the next reboot. It gets a little exhausting. Hellboy sidesteps that.

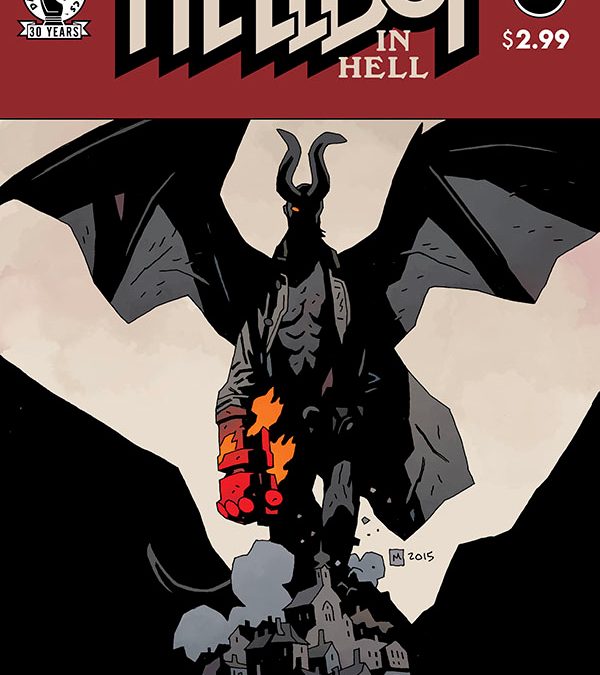

You can die in Hellboy and keep moving right along – it’s a natural built in element of the story that is narratively as clever as the regeneration of The Doctor in Doctor Who. But it’s not like anything was ever going to get any simpler for Hellboy – over the years the complexity of the mythos and all those prophecies about him have stacked up – the movies were great, but in many ways failed to convey the depth and pathos of the books. The covers tell this story – Mignola and the other artists are great at creating iconic images that just draw you in – comics are in a way the easiest thing to market, because they have the text and graphic element there already, and the traditional cover format makes it a little like a poster from the get-go.

So, how do you bring it home? How do you end the huge journey of a character that some people have grown up with, and one who has had highs and lows to the degree that Hellboy has? Mike Mignola, his creator has said that the design of Hellboy In Hell was supposed to make it possible for him to roll along indefinitely telling little interlinked stories or maybe standalone stories with Hell as the backdrop. And somewhere it changed. But the ending arriving isn’t necessarily a total surprise, and some kind of resolution has been called for from the start.

The tone is different in the two books of Hellboy In Hell – this latest one even more so; a finality and almost a tiredness, seems threaded through the narrative and resonates in the color pallet Mignola uses. In order to end you have to do something different – this is an idea espoused by Mignola about his own career it seems, and about the workings of the book and Hellboy’s solution to resolving the fate decreed to be his. It’s a muted somber affair, with some amount of hope in it. You read it, and you leave Hellboy where he’s at, and it feels like one of those goodbyes where you aren’t quite sure what to do with yourself.

Mignola will draw more Hellboy, but for the moment it is going to be stories dealing with his earlier life. There is something satisfying about having a somewhat finite arc to a character’s story. X-Men will never end, nor will Batman or Superman. Grant Morrison who has written both those titles, and much more, would say that this is the great thing about these characters … that they transcend the boundaries of traditional stories and transcend the writers who give them their voice.

How do you perpetuate that kind of thing indefinitely though? It is a problem in serialized TV too – keep it rolling like a juggernaut, and at some point, unless you are very lucky, there is going to be a point where character or narrative logic is sacrificed to escape the accepted format of beginning, middle, and end. I liked about Babylon 5, something of an anomaly in TV, that it planned for 5 years and told a complete story that reached a conclusion. Star Trek with its episodic format and reset button lacked a lot of oomph to its stories because the storytelling didn’t build from episode to episode and develop the characters much beyond that initial view you got of them.

Hellboy isn’t a character that escapes anything set up in previous stories – they all gain weight, and they often come crashing in on him. It is something that should be celebrated and marketed more, because it does lend itself to more meaningful stories, and an arc that really allows the character to develop. Does this ending for Hellboy lose some of it’s impact because Mignola is going to be telling earlier stories? Is it lessened by the possibility that Hellboy is a character who, even after death, still has places to explore and things to do? Read it – I don’t think that is the impression you will come away with. It is an interesting experience – one not really explored in the series itself before, and one not really visited in any other comic book series that immediately spring to mind. Who would have thought that ending a story would be such an interesting phenomenon, and a thing which could be used to market the story?